I was recently asked to think about what I wish I had known on day 1 of my PhD. As a few friends, a flatmate, team members are about to embark on a PhD, I thought of sharing my thoughts and lessons learnt so far. Overall, I think the one thing I’d go back and tell myself is: make mistakes, make them early, learn from them and move on because a PhD is about choices, changes, and challenges.

On a more practical level… When I first started my PhD I did a lot ‘training’ and one thing that stuck with me was that doing a PhD is becoming a project manager: so learning how to mange resources, time, and people.

DISCLAIMER:

I’m at the end of my 3rd year so I’m sure I’ll learn a lot more between now and submission, What I’ve included here is stuff I’ve learnt from my own experience, from talking to other PhD students and by listening to my supervisor. Not everything came easy, some things I had to learn the hard way and others I’m still trying to master.

About YOUR RESEARCH

- Write from day 1. The sooner and more you write, the quicker you will think it’s less dreadful to get feedback. Emotional attachment to your own writing is a thing. Writing a lot, will also help avoid writer’s block.

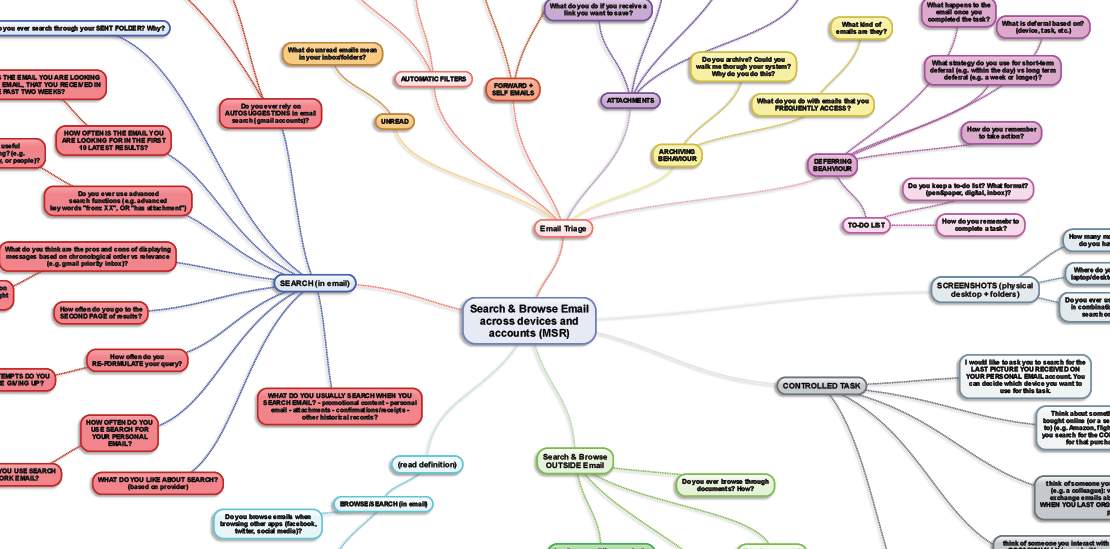

- Start small. If you can, and your supervisor agrees, when you start actually doing research, pick something small to begin with to get your hands dirty and get a feel of things. When starting your data collection, especially if this involves people, there are all sorts of nitty gritty things you want to master quickly but you also don’t want things to go wrong when you’ve just started a year-long trial/study and it’s too late to go back. Starting small will also take away the pressure of having to do everything right. Talk to your supervisor first, but it could be that this first study never makes it to your thesis, depending on your results – and that is fine.

- Publish and Present. Even if it’s a workshop paper, or a talk in your small research group. Presenting your work to other people, verbally or in written format, is the best thing you can do. It forces you to think what is the message you are trying to get across. Take part in as many opportunities you can. And don’t underestimate how long a talk takes to prepare. Also, go to a doctoral consortium. Two if you can. You can read more about why it’s a good thing here.

- Keep a diary. No, not about your feelings and what you did yesterday (well, that too if you want), but one that helps you document your thoughts and it’s all in one place. I use a Moleskine one, because I can’t tear pages out, so I can trace back how my ideas have changed over time. I also have another one that I only use for stats and data analysis. In that one I write what I did and why. You will thank yourself in a few months/years time when you have to resume that data and have no clue what was done. But there it is: Past-You wrote it all down 🙂

PIM (Personal information management)

- Figure out a way to sort your references and be consistent. I re-name all pdfs with “(surname year) title”. I then use tags to colour code refs in Finder on my Mac. Tags can be new refs I want to remember to include in a publication, things like ‘methods papers’ or by topic. You will read A LOT of papers and it’s hard to remember who wrote what. When I’m looking for inspiration or I just want to check in with related work, I just scroll through a particular tag to refresh my mind. Also, pick a ref manager, learn how to use it, and make it yours. You could organise your refs directly there – I didn’t do it from day 1 so I had too much of a back log to catch up with and now I know only use it to include refs when I write a paper/thesis.

- Structure your files. Don’t save files with ‘data’ or ‘data_final.23’. Think about organising files in a way that would make sense to someone else viewing them. Here’s another reason why to do this: it saves you time at the end.

- Get a PhD manual – there are several ones out there. I bought this one, and then ended up getting loads others. They are good to have on your bedside table. Every time you read it you will notice something different, depending on the stage you are in. Also, think about getting a manual to guide you in your research approach (e.g. how to do qualitative analysis, etc.)

- BACK UP. I’ll say it again, back up. In multiple places. Multiple times. Getting something like the Airport time capsule is a good investment. Your laptop will crash, your data will get lost, or your laptop might get stolen.

CAREER DEVELOPMENT

- Document your every step. Create a CV that contains absolutely everything. If you add things as you go on, it will be easier to keep track. Then when applying to jobs, cut the bits that are irrelevant for that position. Have a public profile: be this on your university page, or your own website. Once you meet someone, if they want to know more about you, they will most likely google you. Have a Google Scholar profile. Document your failures too. Here’s why.

- To teach or not to teach? Being an academic means you will have to do some teaching at some point. Being a PhD means you usually have the luxury to decide whether to teach or not. I would recommend doing some teaching, start with something that doesn’t take up too much of your time and take it from there. I personally prefer teaching on different courses to gain more insights on ways of teaching and students. I then have a notebook (the same one I use for my PhD ideas) where I write down things that went well and that I think could have been done differently. There are forms of ‘teaching’ you can do, depending on your department. Being a personal tutor or supervising M.Sc. projects are other options, both valuable. MSc projects are a good way to get some more data on something you are interested in but wouldn’t have the item to do. It also helps build your skills and broaden your research projects. Discuss with your supervisor whether it’s good for you to do it.

- Keep an eye on your peers. My brother and I started our PhDs at the same time and he’s nearing submission in a month (I luckily still have a year-ish). In a recent chat we were having he admitted he had no idea what kind of preparation his peers had. This was made more difficult by the fact that he’s studying American law in Italy and the two countries have completely different ways of doing a PhD /research. As he starts thinking about a post-doc in the US, he doesn’t know how much teaching experience, publications, etc. his American peers have. When going to conferences, seminars, and the like, talk to peers. Not just about research but also about skills, training and experiences. Check their websites. It’s not a popular thing in every discipline, but find out on university web pages what people do. These peers are those that will be reviewing your papers, that will be organising conferences, and that hopefully, one day will be inviting you to give talks and collaborate on grant proposals.

SOCIAL skills

- You are part of a community. Get to know it. This may be the broad community / big conference but it could also be a specific group on your topic. Some are networks and consortiums, others are #hashtags on twitter. But find out what are the Facebook groups to be part of, or Twitter profiles to follow. Lots of useful conversations happen there. Here you can find a few. Community also includes your peers and fellow PhD students in your dept. Talk to them, go to lunch/coffee with them, share stories, make sure you don’t feel alone. You could organise a Write Club as a way of seeking support (again, because you should be writing from day 1).

- Learn how to network and how to ‘work a conference’. It might get easier later on, once you’ve done some research and have something to talk about. Here’s what I learnt in my first year. But the most important thing is to be yourself. You don’t always have to talk about work or research – it’s nice to just have a friendly chat with someone, even if it’s about your favourite coffee shop.

- Volunteer. You are part of a community and you want to be known. Become a student volunteer at a conference – it will allow you to get to know your peers. Review papers – you will find out what others are working on, but also understand how the process of publishing works. Don’t be harsh, be constructive. Write a review that you would be happy to receive.

PERSONAL skills

- Nurture your supervisory relationship. Learn how they can help, learn about their strengths and weakness. We are all human. They are there to help and they want you to succeed. So work on making that relationship work. But also, learn to manage your supervisor. Remind them to send you that feedback, but be respectful of their time. If you’ve submitted something late, accept the fact that they might not have enough time to review your work as you wanted them to. It might not always work out, so if that is the case, have a good think about whether you want to change supervisor. It should be a win-win situation.

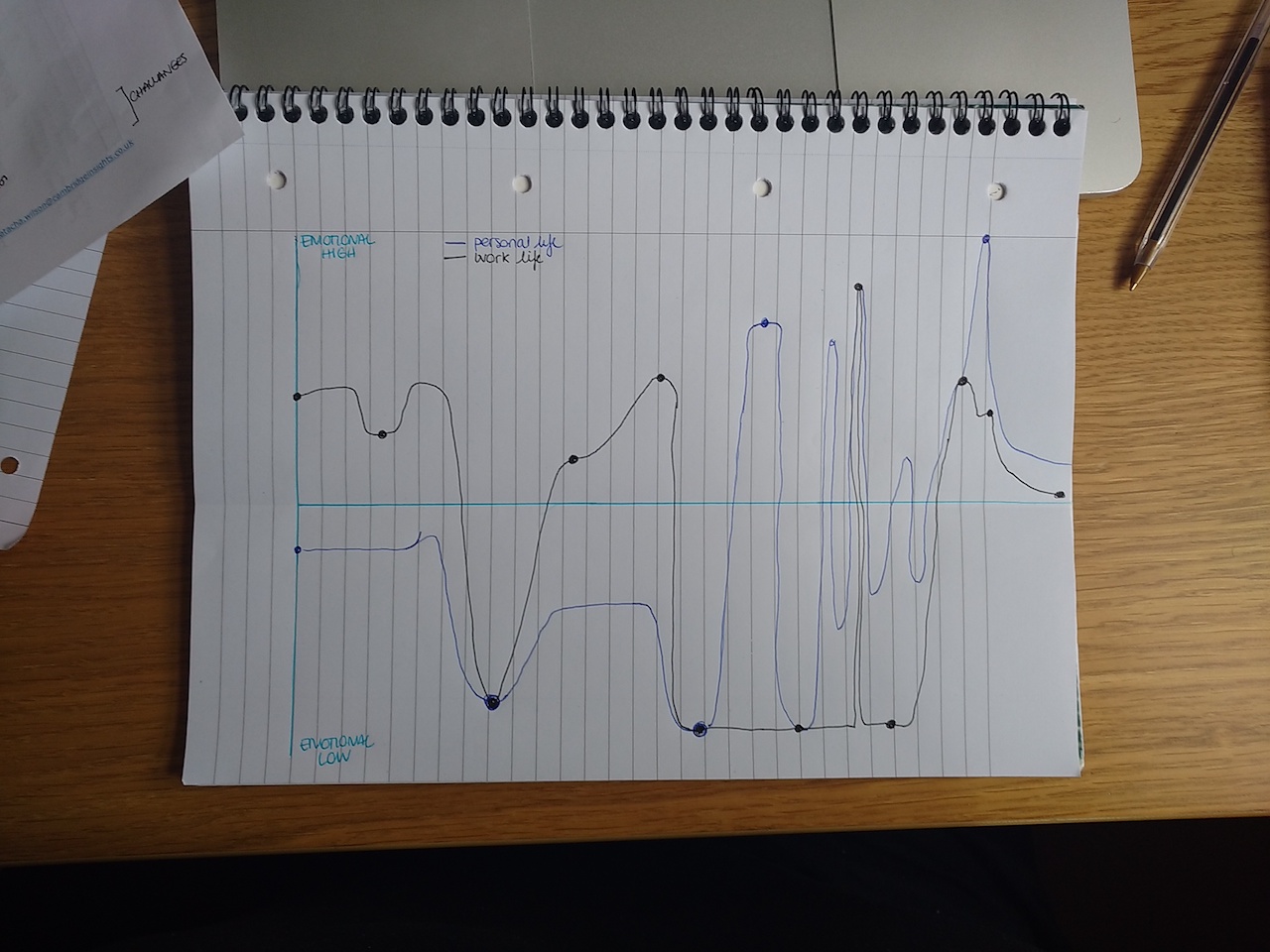

- Look after your mental health. Doing a PhD, in my experience, is maybe the worst kind of roller-coaster. The ups are fantastic, amazing, you feel on top of the world, but the downs are equally as bad. There is an article that describes it way better than I ever could: The valley of shit. Read it, print it and re-read it when you hit the lows. You are not alone. Every university has some sort of psychological support. Talk to your supervisor, talk to your peers. Go for a run, learn what makes you feel good. Doing a PhD is as much as becoming an expert in your field, as well as becoming an expert at knowing yourself. Taking time out, go on holiday or make sure days off are really off.

- You will experience the imposter syndrome. We all do, and for some of us it never leaves you. It’s ok, just know that you have a right to be where you are and you are good enough.

- Learn how to manage your time. I will admit I haven’t quite mastered this one yet, but I’m improving. This is not just about learning how to be productive, but also learning when it’s time to work and when it’s time not to. You are trying to do you research whilst managing refs, as well as preparing papers and talks, but also finding time to teach and supervise, along with reviewing papers, volunteering and networking, you can see how it can be very easy to forget about looking after yourself. Learning to manage time means:

- Learn when you should be saying yes to things, and when you should be saying no.

- Learning that it’s ok to stop and taking an extra 30min to fix yourself a healthy meal, rather than microwaving that mac n’ cheese ready meal.

- Learning that you are quick at doing some things, but you might be slower at others and that’s ok. Spend time understanding how much it takes you to do things (this will change as you get better). There are several tools to help you: you could track your productive time, or you could write down how much time you think something will take you, and then how much time it actually takes you, and compare.

TOOLS

Last but not least, a few very practical tips, most of which I learnt from here:

- Sign up to google scholar alerts.

- Consider buying extra online storage (e.g. Dropbox)

- Get analysis tools. Student versions are cheap or your Uni might have access to them for free.

- Buy a VGA cable and a presenter stick.

- Buy an external hard drive.

0 Comments