As part Northumbria’s university-wide strategy to move all meetings online, we have also moved our fortnightly NORTH Lab seminar to be remote. NORTH Lab is an interdisciplinary research collecting within Northumbria that brings together people from Computer and Information Sciences, Design and Psychology, among others. This week, rather than holding our usual talk, John Rooksby organised an online panel on how HCI knowledge and collective power can be used to tackle the coronavirus crisis. We had 5 panelists and almost 70 participants from all over the world. I’ve summarised what was discussed by each panellist below and the conversations they sparked, along with some personal reflection on the overall experience. Hopefully I’ve not misrepresented anyone’s work. At the end of the post, you’ll also find a bunch of resources that were mentioned and shared.

Prof John Vines (Northumbria) – Social isolation & loneliness

Loneliness, while often transitory, can lead to chronic conditions, and be frequently present in older adults. However, we are witnessing a multitude of situations where we experience loneliness in the course of our life, not least with this recent global health crisis.

John has been working on the LIDA project, which explored the role of technology in amplifying and mitigating isolation and loneliness among three populations. Firstly, they found that retirees experienced a rapid loss of empathic relations, so developing asynchronous social technology (or phatic technology) could be a way of keeping older adults connected. Secondly, new parents, who were generally well connected, had suspicions around social apps like Peanut and services where you “pay for friends”, because such resources tended to normalise what was considered a good or bad form of parenting. Nonetheless, they found that having tools that simply made new parents aware of other hyper-local parents was enough to provide social reassurance. Finally, the third group they looked at was community-based telecom engineers who worked remotely and no longer accessed the depot. This group generally did not feel lonely, but still longed for conversations with colleagues when deployed in the same venue. They also appropriated the surveillance technology used by their organisation to arrange shared remote meal times.

What this research shows us is how HCI can provide a positive response to social distancing, which should actually be reconceptualised as physical distancing, where social distancing is a sub-risk. This global crisis might be an opportunity to rethink, from an HCI perspective (but not only), what “social” means today. However, should this be a research opportunity? Should we be creating interventions to support social connection? Not necessarily. This is certainly an opportunity to learn and one for practice.

Dr Santosh Vijaykumar (Northumbria) – Misinformation & older adults

In this global crisis, older adults are among the most vulnerable population, not just because the over 70s are at greater health risks for covid-19, but also because older adults are most vulnerable to misinformation. From a psychology research perspective, one of the reasons that makes older adults more likely to be subject to misinformation is that they experience cognitive decline and there is greater confidence in false memories. In addition, once knowledge is formed, this resident knowledge guards them against believing new claims for which they already have prior information about. Finally, the more they are exposed to the same false claims for which they have no prior knowledge of, the more likely they are to believe them.

In relation to covid-19, there are several examples of misinformation and fake news that have been going around already, such as the claim that Daniel Radcliff has coronavirus. More worryingly due to the socio-political implications, an audio recording was shared amongst attendees that has been going around WhatsApp claiming the military will be on the streets in Ireland on Monday at 2pm, claiming this insider information was being passed on by someone’s brother’s friend. Research around the motivations behind spreading fake news could help shed some light, along with what platforms exists to debunk such stories. What counts as trusted becomes very important and an interesting issue to unpack, especially how the provenance of a “trusted” source is understood.

As a result, it is paramount that health-related data literacy interventions need to be first created, and then monitored and evaluated for the future. However, it’s hard to say if these need to be specific for older adults. There are two aspects we should be kept in mind when developing and evaluating interventions for them though: firstly, that if older adults see value in using a new piece of technology, they will adopt it; secondly, that it is possible to engage at a rational level with older adults and they are receptive to unpicking fake news and other forms of misinformation. Therefore, two key questions for HCI research at the moment looking at tackling misinformation online are:

- How feasible is it to build (nimble and quick) data literacy interventions for older adults to cope with covid-19 misinformation?

- What kind of design innovations can we develop to inoculate older adults from health misinformation in the future?

Prof Anna Cox (UCL) – Remote working & work-life balance

Under normal circumstances, working from home should be simple. Anna is on day 1 of 14 in self-isolation. She joined from her living room, with her two kids – also in self-isolation – in the same room, and despite her experience of working from home on a weekly basis, the current situation is still proving challenging.

From her perspective, there are several key question we can ask as HCI researchers. First, how can HCI inform guidelines and provide evidence-based strategies? Research on working practices of crowd workers such as Amazon Mechanical Turks shows that people don’t have these nice office set-ups, secluded in some part of their house. Instead they often work from their bedrooms or living rooms, whilst looking after children. We also know that technology impacts our work-life balance by blurring boundaries, but in this current crisis with most schools closed and people being thrusted into Working from Home, there are no boundaries. In addition to checking social media and the news, we are getting messages from colleagues, which just add to the notification overload and distractions we experience daily. While most research on interruption is focused on the office environment, what new and different distractions do we experience at home, in this particular climate?

Moreover, how are people going to cope with disconnecting from work? Work recovery is an important part of productivity, but while research shows that playing video games can be a good strategy for work recovery, there are other situated factors that come into play with covid-19. People are worried about our own health and that of family and friends, plus with rapid changes in the workplace, disconnecting becomes more challenging.

Therefore, what are new ways to connect with one another, create entertainment and being/keeping well, both mentally and physically? The media is often reporting worries around screen time for children, but the reality of having to work from home and managing childcare means that many parents’ rules around tech use is likely to change and be more relaxed in the coming weeks and months. This only emphasises the need to not ignore the positive aspects that the digital brings. However, we need to be mindful and more aware of the limits in applying what we already know to this current situation. There are definitely parallels with history (e.g. pre-industrial revolution many would live above their shop), which can offer an interesting lens on how to cope today. The difference now and the major difficulty is how rapidly the transition to working from home is happening.

Dr Angelika Strohmayer (Northumbria) – Caring for the marginalised & vulnerable

As a researcher, Angelika has taken a series of decisions to pause all in-person data collection and offer her expertise as support and help, without overpromising. This is something that we should all be thinking about.

What this pandemic is quickly highlighting is how our understanding of who counts as vulnerable is malleable, especially in relation to social (physical) isolation. For example, gig workers such as Uber and Deliveroo workers are suddenly even more vulnerable. Deliveroo has announced they will be launching a no-contact drop-off feature that customers can activate if they don’t want to expose themselves to health risks. However, this feature is not protecting the riders themselves.

For many others populations, there is an increased risk of digital exclusion. For example, some may rely on drop-in sessions as their only positive point of contact in a week – how will policies of social isolation impact them? The decision of local libraries to close can mean that those in the UK to need to access benefits are suddenly cut off because they do not own a computer and the library was their only option. Other vulnerable groups that risk exclusion from health services include refugees and asylum seekers, who might be afraid to report their symptoms for fear of being deported. It’s hard to know what is the best way forward to support such populations and there are indeed more questions than answers.

However, Angelika also raised a key question around how can HCI promote compassionate solidarity? Her suggestion is through building community. This means both within our own personal and professional networks, but also thinking more broadly. For example, she has been involved in developing a Rapid Response Research toolkit. While this sparked as a result of children being separated from families at borders in the US, the work has continued through a series of hackathon evenings, particularly around supporting existing responses. More importantly, now seems the time to rely on our collective knowledge on how to create and sustain peer networks on social media and asynchronous communication channels? What is the additional work that someone needs to do to implement this? Tools that previously seemed meaningless, like Nextdoor.co.uk, suddenly may be more appealing as they offer an opportunity to connect with neighbours and check in with one another.

Dr Jacki O’Neill (Microsoft Research India) – Social responsibility of HCI researchers

Following on from Angelika’s discussion on vulnerable populations, Jacki’s current research has been involving auto-rikshaws drivers in India who receive little to no social support, have already seen a 50% reduction in business due to covid-19 and less than a quarter of these workers have some savings. As researchers and industry practitioners, can we help support these vulnerable groups in lobbying the government? One way is to organise fundraising sites to help people who are losing salaries, but to rely on disaster relief organisations (the same ones who delivered groceries in China during the lockdown) to coordinate these efforts in order to avoid mishandling of donations and money, especially as a result of unregulated fundraising. This is an issue that might need to be considered more globally, as fundraising campaigns pop up around the world to support local hospitals and other key workers being affected . Another form of support is to increase the number of delivery drivers, who in India are a very large group, and that companies such as Amazon are already thinking about with a hire of 100thousand deliver and warehouse workers. This is where auto-rikshaw could be hired to do such work, to help maintain their salaries.

Jacki also called for rethinking how our specialised knowledge around remote work can help us understand the current situation, because our current CSCW understanding does not address the situated reality. Jacki has been working from home for the past 1.5 weeks, in a 3-bedroom house with 7 people. This makes it hard to concentrate. There is a need to rethink how we connect and disconnect from work, and also ways in which we can escape one another when in close proximity.

One final point she made – and one that is very important – as HCI practitioners if we want to do research around the impact of covid-19 we should not become disaster tourists and we should be mindful of the time of professionals. There are ethical and moral implications we should be considering – is it better to be a researcher now or is there something more practical that we should be doing, wearing our human hat?

The value of remote HCI connection

It is safe to say, this remote panel session was extremely valuable and a success! Kudos to John Rooksby for organising it in such a short time.

While I can’t speak for everyone, I found it particularly helpful to see colleagues and other researchers share their experiences in a human, yet critical and evidence-based way. It definitely helped reduce my stress levels, which – with half my family in Italy and half in the US – has been skyrocketing.

More importantly, it broadened our ability to discuss with others with whom we would not otherwise be able to, if not in rare occasions such as at CHI. And given that the physical CHI is cancelled this year, being able to connect with researchers like this is a great opportunity. Whether this should be continued long-term or we should prioritise nurturing our local HCI communities is something that needs to be explored as the weeks unfold.

It was also suggested that for such meetings and get-togethers to be really meaningful, it’s worth thinking about what we want to get out of them and perhaps setting a goal. While I’m not against it, after having spent 1.5 weeks in social isolation due to first having a cold and now being considered at risk because pregnant, I missed having human connection that wasn’t just my husband or my family over WhatsApp video calls.

The rapidity of changes to our working lives and the insights that this 1.5 hour brought of our new normal was comforting: seeing vacuum cleaners in the background, makeshift offices in children’s nursery rooms, people propped on sofas, and how often we all touch our faces is incredibly reassuring. I also learnt that my husband and I cannot schedule videoconferencing calls at the same time in the coming weeks as our wifi is not strong enough.

🧼Wash your hands people! 🧼

and take care

Relevant resources

- Doing fieldwork in a pandemic

- #viralkindness postcard to offer help to neighbours

- A historical perspective on social distancing – the case of the Spanish flu

- The challenges of students having to hop on online lectures

- Torn apart project

- Evidence based strategies for managing work-life balance

- Covid-19 open research dataset

4 Comments

How can HCI research(ers) address the coronavirus crisis? | Part 2 - Dr Marta E. Cecchinato · 25th March 2020 at 7:44 pm

[…] NORTH Lab panel on HCI research for covid-19 this week. Following on from last week (you can read a summary of the first panel here) It was nice to be joined by another 60-ish people, this time mainly across the UK and Europe. And […]

How can HCI research(ers) address the coronavirus crisis? | Part 3 - Dr Marta E. Cecchinato · 2nd April 2020 at 12:53 am

[…] on from Part 1 and Part 2 of our NORTH Lab online panel series, below are my notes on yesterday’s […]

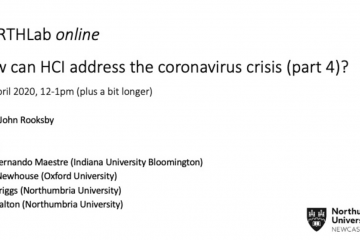

How can HCI research(ers) address the coronavirus crisis? | Part 4 - Dr Marta E. Cecchinato · 9th April 2020 at 3:45 pm

[…] to Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3 of our NORTH Lab online panel series, I’ve once again summarised the […]

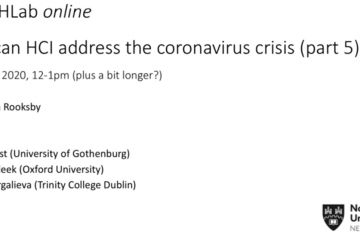

How can HCI research(ers) address the coronavirus crisis? | Part 5 - Dr Marta E. Cecchinato · 20th April 2020 at 5:07 pm

[…] attend in real time the last of our NORTH Lab panels on covid-19 and HCI research (see summaries of panel 1, panel 2, panel 3 and panel 4), but thanks to technology I can still report back on what was […]